What happens to asphalt when oil refineries shut down?

As the global energy landscape shifts toward decarbonization, industries reliant on petroleum-derived products face both challenges and opportunities. One such critical product is asphalt binder, the glue that holds together the world’s roads, runways, and infrastructure. A recent report by the Asphalt Institute Foundation and Wood Mackenzie, titled Analyzing the Petroleum Asphalt Binder Supply Chain under Energy Transition Scenarios, offers a comprehensive look at how the asphalt industry can adapt to a low-carbon future.

I do some work in the sector so I needed to digest the full report, this article tries to summarize the report’s key findings and perspectives for readers who won’t spend hours reading a long technical paper but want to understand the implications for infrastructure, emissions, and supply chains.

Asphalt Binder: A Critical Product from a Marginal Stream

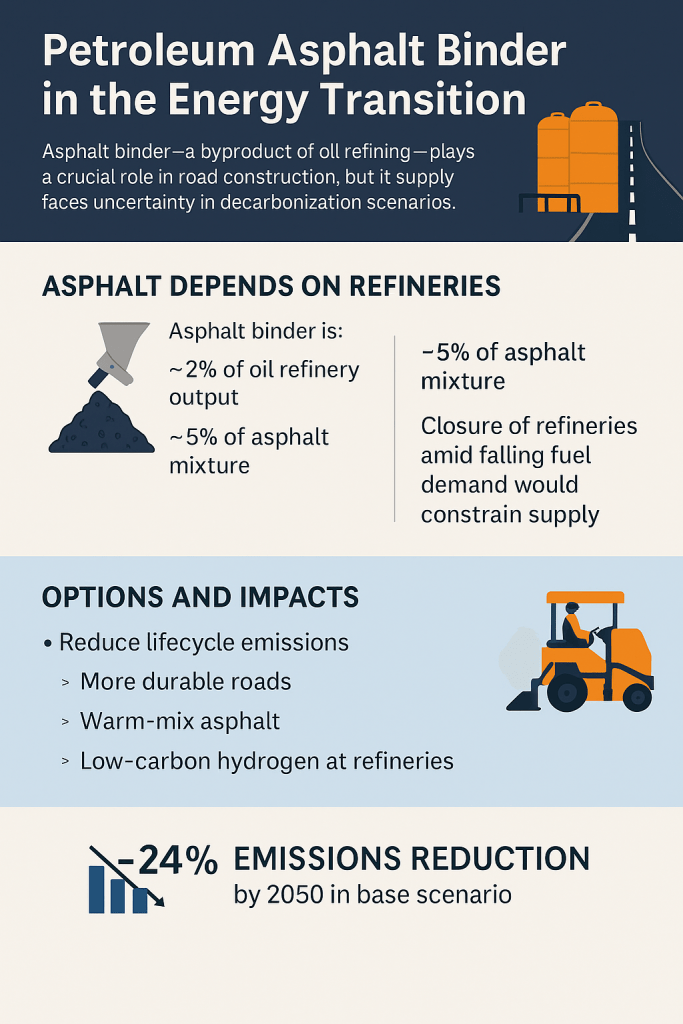

Asphalt mixtures—the material used to pave roads—are roughly 95% aggregate and 5% asphalt binder. While this binder is essential, it represents just 2% of the output from a typical oil refinery. This small share makes the asphalt supply chain vulnerable to shifts in refining priorities, especially as the energy transition accelerates.

Most oil refiners optimize for high-value fuels like gasoline and diesel. As demand for these fuels declines due to electrification and improved fuel efficiency, many refineries may shut down—potentially straining asphalt binder supply. With asphalt providing the backbone of over 94% of the United States’ 4 million miles of roads the continued supply matters when it comes to maintaining our critical transport infrastructure.

I can hear some of you thinking out there, “so what, just use concrete.” Well that would have a lot of other implications in terms of costs and practical application but concrete also comes with much higher carbon emissions. If this is playing out as a result of reducing emissions it would seem silly to cut one area only to find they increased by even more than those cuts by using the other material.

Three Scenarios, One Key Risk

Wood Mackenzie modeled three energy transition scenarios:

- Base Case (2.5°C warming) – The most likely scenario, with modest refinery capacity reductions.

- Pledges Scenario (below 2°C) – Reflects stated net-zero pledges through 2060.

- Net Zero Scenario (1.5°C) – Assumes aggressive, full-pathway decarbonization by 2050.

| By 2050 | Refinery Capacity | Asphalt Binder Gap (North America) |

|---|---|---|

| Base Case | Largely intact | No supply shortfall |

| Pledges | Moderate decline | 55,000 bpd gap |

| Net Zero | Severe contraction | 205,000 bpd gap |

So in summary if we do little to nothing about carbon emissions from refining and road transport fuels then there is nothing to worry about. Ok, well maybe that means there is certainly plenty to worry about, but asphalt supply isn’t one of those worries. If on the other hand we do transition to a net-zero world, supply from refineries alone could fall short by 50%. That raises the relevant question: how will we pave our roads?

Can Emissions Be Reduced While Meeting Demand?

Compared to concrete, asphalt has a lower emissions intensity, and emissions from binder use are significantly lower than transport fuels because it’s not burned. Still, asphalt production is energy-intensive across its value chain—from mining and refining to paving and maintenance.

A key insight from the study: Cradle-to-gate emissions are not the full story.

Wood Mackenzie evaluated cradle-to-grave emissions, factoring in road performance and maintenance. Their findings:

- Cradle-to-gate emissions for paving a one-mile lane: ~222 metric tons CO₂e.

- Cradle-to-grave emissions including use and end-of-life: ~505 metric tons CO₂e.

Designing roads for durability can dramatically reduce emissions. For example, using more durable mixes or regular preservation techniques can lower lifecycle emissions by up to 20%.

Pathways to Lower Carbon Asphalt

Reducing asphalt emissions will require action across the entire supply chain. Key strategies include:

Upstream

- Reduce flaring and leaks during crude oil extraction.

- Electrify drilling and implement carbon capture for oil sands.

Refining

- Shift to low-carbon hydrogen and electric heating.

- Reoptimize yields to favor binder over transport fuels.

Asphalt Plants

- Adopt warm-mix asphalt to reduce heating needs.

- Use natural gas or biofuels instead of fuel oil.

Paving Operations

- Transition paving equipment to biodiesel or electricity.

- Improve preservation strategies to reduce lifecycle emissions.

Under the base case, a 24% reduction in emissions is possible by 2050. Under more aggressive transition scenarios, reductions of up to 58% are modeled—but only with systemic changes across both industry and policy.

Supply Solutions for a Low-Oil World

To bridge potential supply gaps, the study analyzed several options:

| Option | Viability | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Refinery Yield Shifts | High | Requires economic incentive, operational changes |

| Refinery Conversions | Moderate | High capital cost, crude sourcing |

| New Standalone Facilities | Moderate | Expensive, scale constraints |

| Recycling Binder | Moderate | Performance limits at high mix levels |

| Bio-based Additives | Low to Moderate | Costly, supply limitations, performance concerns |

| Increased Imports | Low | Infrastructure and supply security issues |

The most promising near-term option is shifting yields at existing refineries—diverting heavy residues from fuel production to binder manufacturing. But longer-term solutions may include new production models and more sophisticated recycling.

Takeaways from the Field

Interviews with refiners, contractors, and agencies offered grounded insights:

- Durability remains king. Low-carbon alternatives must match or exceed current performance to gain widespread adoption.

- Cost sensitivity is real. Without stronger policy or customer demand, premium-priced green solutions face limited uptake.

- Policy may be key. Warranty-based procurement and emissions transparency (via Environmental Product Declarations) could shift incentives.

Final Thought: Planning for Resilience

The energy transition creates risk—but also opportunity. Asphalt demand isn’t going away. But the pathways to secure, sustainable supply are evolving. Whether it’s retooling refineries, innovating materials, or refining procurement policies, the decisions made today will determine how well the roads of tomorrow are paved. For those of us in the energy sector, this is a chance to rethink how we produce and use critical materials like asphalt binder, ensuring that the roads we travel are built to last—both physically and environmentally.

For readers interested in exploring the full details, emissions modeling, and scenario analysis, the full report is available through the Asphalt Institute Foundation‘s Research and Reports Section and they have a recorded webinar discussing the report’s findings.

Leave a comment