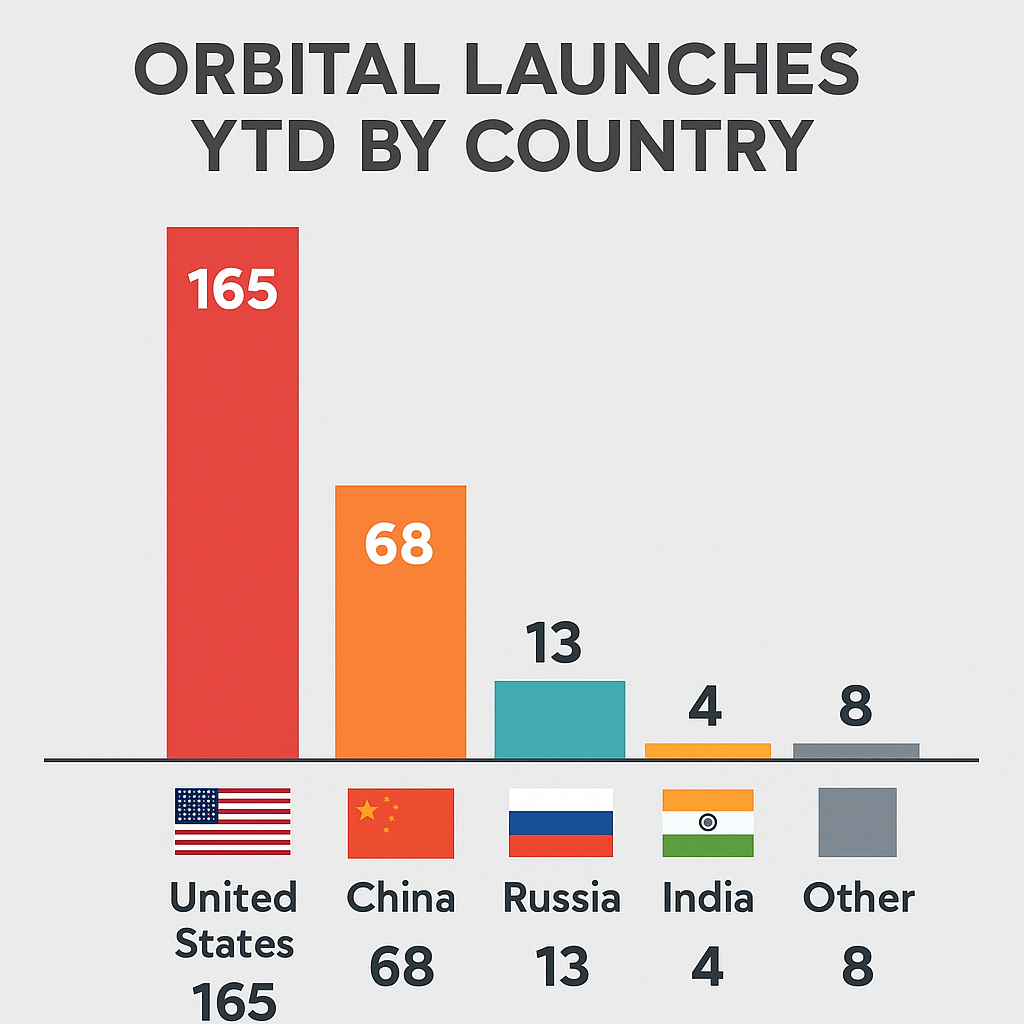

Humanity’s access to orbit is expanding faster than ever. As of early November 2025, there have been 262 orbital launch attempts worldwide which is on pace to surpass the record pace of 2024. For a kid who went to Cape Canaveral to watch the Space Shuttle launch, which was something might happen a couple of times a year, this is kind of mind blowing.

Thanks largely to SpaceX, the United States accounts for roughly two-thirds of all global launches. China contributes another quarter. Together, they have turned orbital access into an industrial operation rather than something that’s akin to a national holiday.

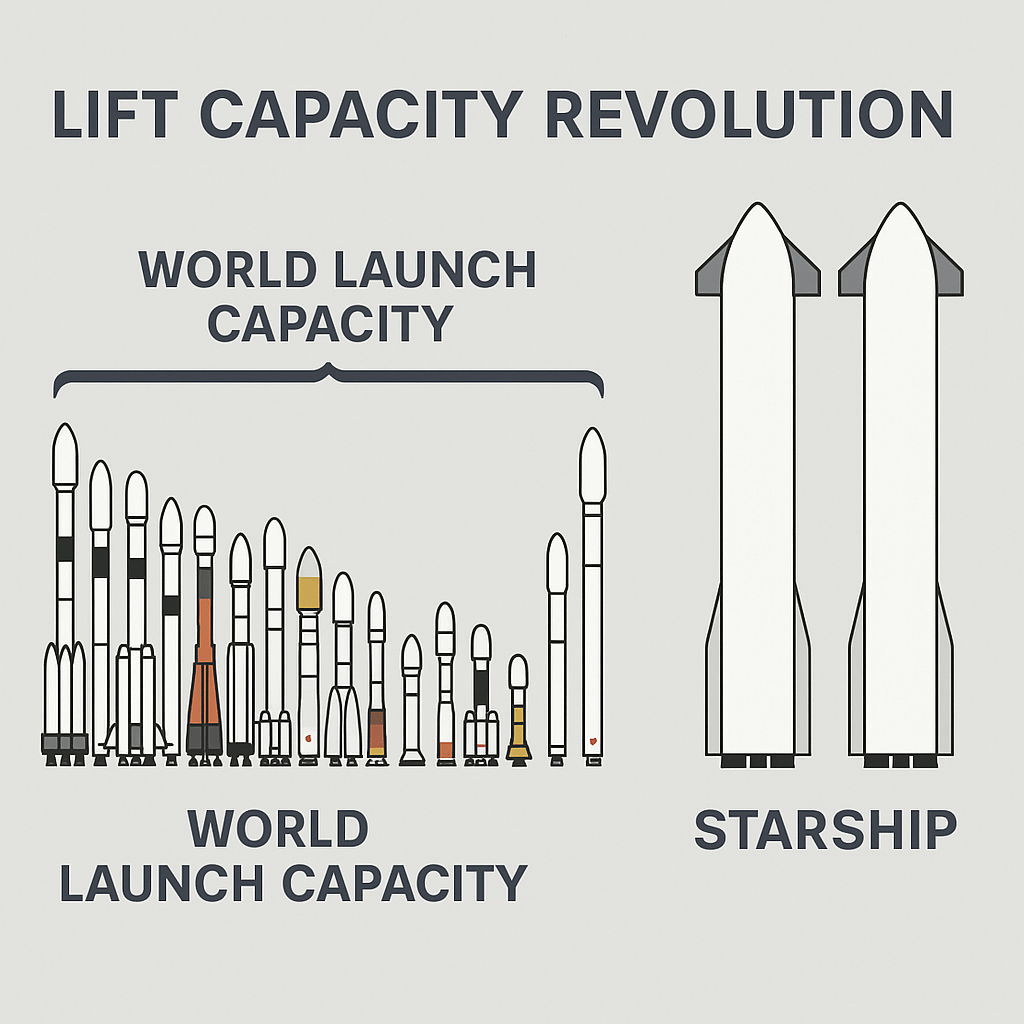

Yet cadence only tells part of the story. When we sum up the lift capacity per year the actual tonnage the world collectively can deliver to orbit, the combined total of all rockets equals between 2,000–3,000 metric tons to low Earth orbit annually. Just a handful of Starship launches in expendable configuration could match or exceed that figure.

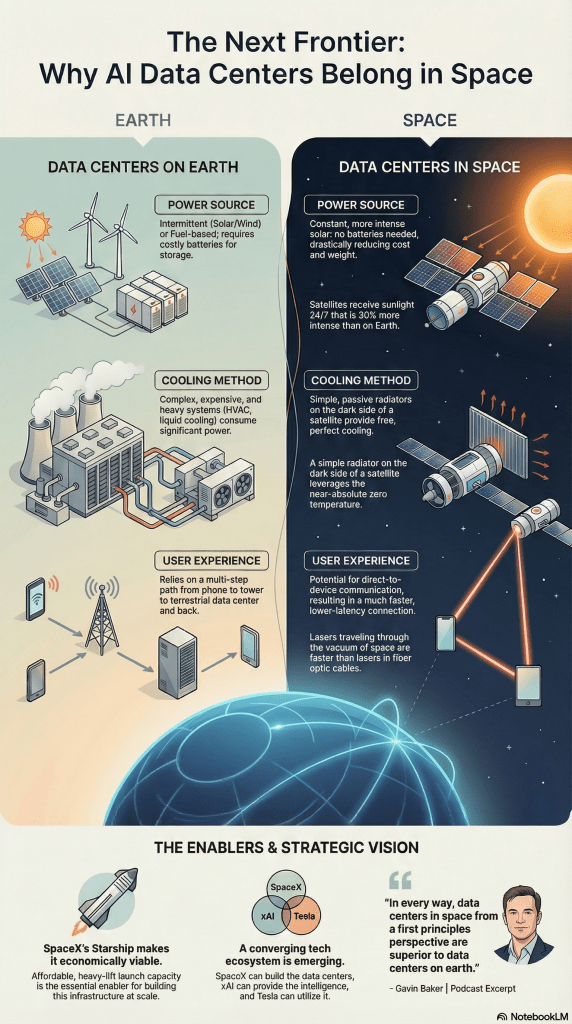

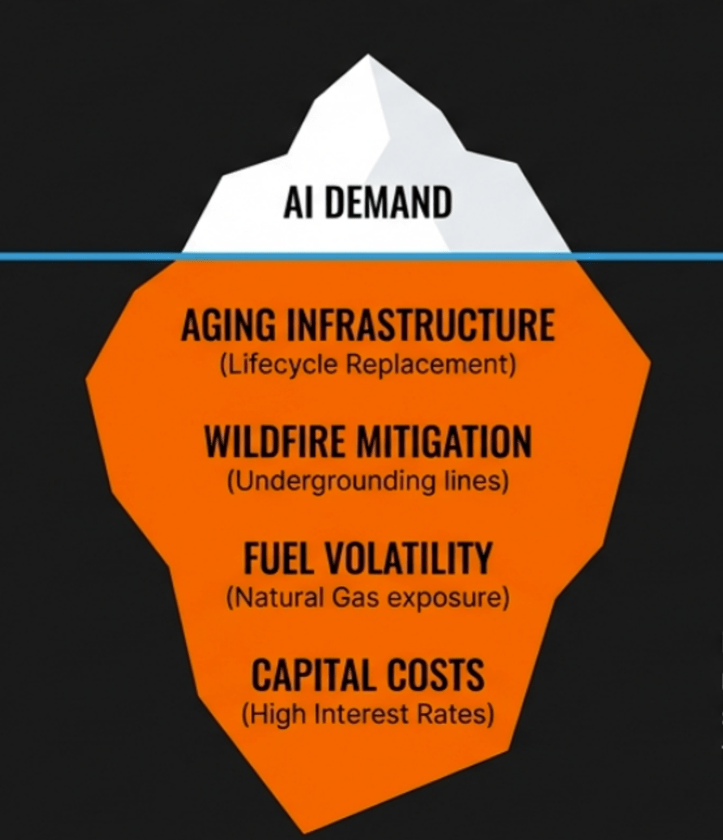

This concentration of capability marks a new phase in the economics of space. The question is no longer whether humanity can reach orbit—it’s what we’ll build once we’re there. As an energy guy who is working on AI and fielding lots of questions about where all the power is going to come from, this really got me thinking about all that solar power being available 24×7.

🚀 The Economics of Lift Have Flipped

For decades, space-based solar power has lived in the realm of thought experiments, experiments that were technically plausible but economically out of reach. Launch costs were too high, arrays too heavy, and beaming power back to Earth too lossy.

Starship’s reusable lift could cut costs by 20–50× compared with today’s rockets, dropping launch below $200 per kilogram.

At this price point, putting high-specific-power solar arrays into orbit starts to look less like science fiction and more like early-internet economics.

☀️ Continuous Sunlight Changes the Game

In geosynchronous orbit, solar arrays receive nearly 24 hours of sunlight year-round. With today’s 30% efficient multi-junction cells and irradiance of 1,361 W/m², that means over 400 W/m² of electrical output, all without worrying about weather or waiting on the sunrise.

Each ton of solar hardware can generate 100–150 kW of continuous power in orbit. Even after conversion and transmission losses, that’s 50–75 kW delivered to Earth—per ton of payload.

Cheap lift converts what was once a one-off engineering marvel into a scalable energy system.

🌍 A Different Kind of Solar Plant

Once you remove night, weather, and land from the equation, the challenge shifts from intermittency management to capex amortization and payback economics.

Some optimistic but plausible LCOE modeling shows:

- At $200/kg launch, $500/kg arrays, and $1/W rectenna, space-to-Earth solar could reach $0.10–$0.15/kWh.

- If the power is used in space instead of beamed down, LCOE could drop to $0.05–$0.10/kWh.

Powering computing or manufacturing directly in orbit could cost less than firm terrestrial renewables.

🧠 Computing and Manufacturing in Orbit

The combination of cheap energy, continuous sunlight, and vacuum could make orbit the next industrial zone.

Imagine:

- AI training clusters operating off continuous solar supply

- Chip or materials fabs leveraging microgravity and vacuum

- Optical data links replacing power cables as the bottleneck

With $0.05–$0.10/kWh orbital power, the economics of compute in space start to rival terrestrial data centers constrained by grid capacity and cooling.

🔭 Why It Matters

- Launch efficiency now rivals module efficiency as the dominant economic lever.

- Energy availability in orbit is constant—redefining what “baseload” power could mean.

- Global lift capacity can scale fast enough to enable serious pilot projects within the decade.

Cheap lift could become the “bandwidth moment” for energy in space. The point when a once-theoretical concept becomes inevitable.

Leave a comment