They say justice delayed is justice denied. But what happens when justice never existed and public dollars vanish into litigation for naught?

A Legal “Big Idea” use City and State resources to extort settlements

In 2020, the coastal city of Charleston, SC joined a wave of municipal lawsuits targeting fossil-fuel companies, most of them calling out defendants like Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP, Shell plc and dozens of other energy firms, alleging that their decades-old business of producing and selling energy contributed to climate change, sea-level rise, flooding, and consequent infrastructure costs the city would have to bear.

Charleston framed the case as a fight for accountability, painting fossil producers as “big oil” villains who allegedly concealed risks and profited while communities sunk under rising tides. For Charleston, my hometown, with a sprawling coast, historic architecture, and increasing flooding pressure, the lawsuit may have seemed like a bold stand.

But beneath the rhetoric, a far less attractive truth would emerge: a five-year drain on public resources, a legal theory repeatedly rejected in court, and a final judgment that stripped the lawsuit of any claim. This final ruling, which the city has chosen not to appeal, effectively ends the fight with a whimper, not a win. Far from a bold stand, by distracting our citizens with theater, and not focusing on real efforts to improve our infrastructure, Charleston has wasted five years of public resources.

The Five Year Litigation Odyssey: From Filing to Dismissal

2020 — The Complaint is Filed

In September 2020, Charleston formally filed suit (Case No. 2020-CP-10-03975) in state court, accusing fossil-fuel companies of torts including public-nuisance, failure-to-warn, trespass, and violations of the South Carolina Unfair Trade Practices Act (SCUTPA).

2020–2023 — Removal to Federal Court, Jurisdiction Clash, Remand

Defendants removed the case to federal court. Over the next three years, Charleston waged a jurisdictional battle — fighting remand, responding to motions, submitting briefs. In July 2023, the case was remanded back to state court. (Timeline of these rulings with links to filings)

2023–2025 — Back in State Court: Merits & Motions

Back under state jurisdiction, the case turned to the substantive merits. But the city’s legal theories began to unravel: courts found that under the U.S. constitutional structure and under the federal Clean Air Act (CAA), state-law suits against out-of-state emissions sources are preempted.

May 5, 2025 — Briefing After Executive Order 14260

In the middle of the case, the Trump administration issued Executive Order 14260, aimed at limiting the ability of states and localities to bring climate-liability claims — adding new pressure on the city’s case. Charleston and defendants submitted a joint response on its implications.

May 29, 2025 — Final Hearing

The last major hearing took place. The scale of participation — dozens of attorneys, court staff, supporting teams — underscored how deeply buried the city had become in procedural and constitutional wrangling.

August 6, 2025 — Dismissal Order

Circuit Judge Roger M. Young, Sr. delivered a 45-page ruling dismissing all claims. The court held that state law claims addressing global greenhouse-gas emissions are preempted by federal law and barred by constitutional federalism; it applied independent state-law grounds too: political-question doctrine, statute of limitations, failure to state a valid claim, and lack of personal jurisdiction for many defendants. (Link to Jones Day analysis on the dismissal)

September 2025 — No Appeal

Charleston chose not to appeal — ending the five-year fight with no recovery, no compensation, and no precedent established. (Other cities continue to waste resources on appeal)

The Legal Theory Failed On All Fronts: Preemption, Federalism, and even State Law

At the heart of the dismissal was a bedrock principle of U.S. law: federal preemption. Through the Clean Air Act, Congress delegated the regulation of greenhouse-gas emissions and air pollutants to the federal government and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Courts have repeatedly held that state laws and tort claims cannot be applied to impose additional liability for emissions that cross state or national boundaries.

Additionally, the court invoked the constitutional principle of federalism: a single state (or city) cannot unilaterally impose liability or regulation on emissions that originate globally or interstate, doing so would undermine the carefully calibrated, the nation-wide regulatory balance Congress created.

Finally, even under state law, Charleston’s core claims failed: nuisance doctrines typically apply to land-use and localized harms, not worldwide emissions decades removed from the defendants’ operations. Failure-to-warn and consumer-fraud claims similarly faltered given the public, long-standing debate around climate change. (Jones Day Analysis)

In short: what began as a “bold” attempt to hold “big oil” accountable ended in predictable legal defeat and a massive waste of time and local resources. This was not just a poor choice for the city to invest in sure to lose litigation, but a failure to recognize that the legal architecture of the United States overall is not designed to treat climate change as a local tort claim.

The Real Cost: Public Resources Spent, But Nothing Gained

I am sure those that approved and participated in this will claim that because they retained outside counsel on a contingency-fee basis, which limited upfront cash payments, the city and by extension, taxpayers didn’t bear the costs of the lawsuit. That position ignores the facts that city and our state courts still invested significant internal resources.

Over five years, public employees in legal, administrative, planning, and communications roles had to dedicate hundreds, likely thousands of hours to the litigation. Court staff, judges, clerks, and administrative personnel across multiple courts were likewise tied up.

Based on conservative modeling of simple labor costs per hour, even without quantifying expert fees, interest, or hidden overhead, the public-resource cost of this litigation likely consumed hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars, with zero return and years of wasted effort.

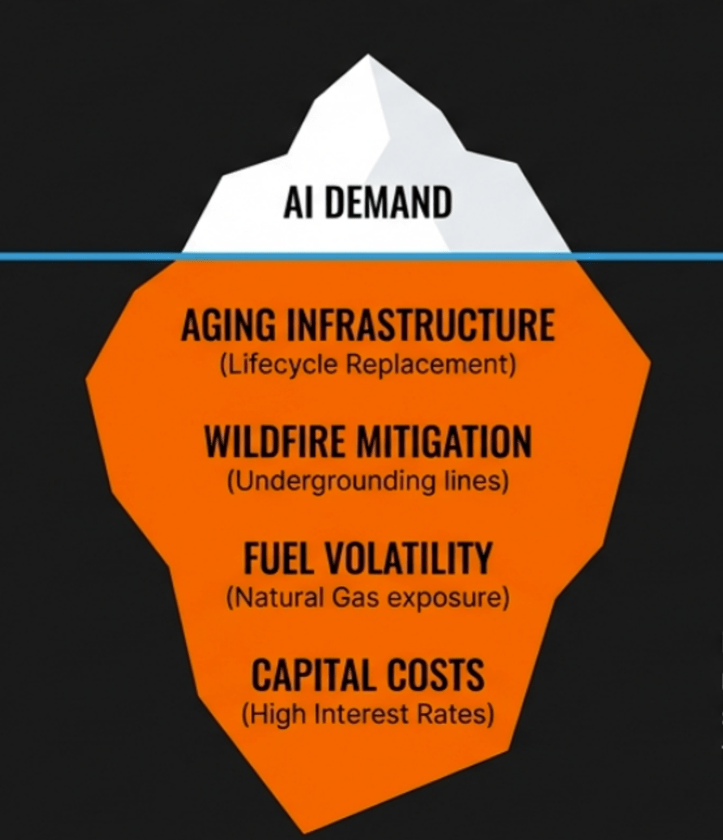

That is a real fiscal cost for a city facing expensive infrastructural and resilience demands.

A Failed Attempt at Litigation-Backed Policy

What this case really delivered wasn’t accountability. It delivered a warning sign about misguided efforts of policy making by lawsuit. When a municipality allows it’s resources to be hijacked by plaintiff attorneys seeking to use their resources to extort business and uses the courts to pursue a broad social agenda against lawful industry, the court of law isn’t the right venue.

This wasn’t about holding bad actors to account. This was an extortive gamble that asked courts to impose economic liability on companies executing lawful business under longstanding federal regulation. The gamble lost.

And now, the public, not some oil company pays the price for five years of distraction and resource drain.

What Should Come Next? Practical, Policy-Driven Solutions not Litigation Theatre

For a coastal city like Charleston, where we are facing sea-level rise, coastal flooding, storm surge, and insanely escalating insurance costs the path forward lies not in lawsuits, but in infrastructure investment, resilience planning, smart zoning, and realistic energy transition.

If local leaders are serious about protecting taxpayers and strengthening community resilience we need them to:

- Direct resources toward adaptation infrastructure (sea walls, drainage, flood-resilient building codes)

- Promote cleaner energy adoption (efficiency, renewables, electrification) without demonizing lawful fuel supply chains

- Engage in federal and state regulatory reform advocacy — where emission standards, energy policy, and national coordination belong — not in courtroom speculation

Because at the end of the day, lawsuits don’t build seawalls. Policy, planning, and engineering do.

🧭 For Further Reading

- Court dismissal opinion for City of Charleston v. Brabham Oil Co. — August 6, 2025. ORDER GRANTING DEFENDANTS’ JOINT MOTION TO DISMISS PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT FOR FAILURE TO STATE A CLAIM AND FOR LACK OF PERSONAL JURISDICTION

- Overview of rising dismissal trends for municipal climate-liability suits. South Carolina Court Dismisses City’s Climate Litigation Against Energy Companies

- Legal analysis of federal preemption under the Clean Air Act and constitutional limits on state-level climate tort claims. Charleston’s Climate Lawsuit Collapse Shows That Common Sense Prevails

- Critical discussion on whether lawsuits are effective for climate protection. Are lawsuits effective ways to protect the climate and environment?

Leave a comment