California refiners are about to face real outside competition. The Western Gateway Pipeline, a new connection linking Midcontinent and Gulf Coast refining capacity to Southern California demand, is not just a logistics project. It is a structural break in the supply basin architecture that has kept California largely insulated from the rest of the US refining system.

California earned a reputation as a “fuel island” not just because it lacked infrastructure, but because what infrastructure there was ran in only one direction. What extra supply there was only flowed east, not west.

California refiners have enjoyed a captive market, reinforced by regulatory barriers and geography. When capacity went offline, prices spiked, and there was no fast way to backfill with supply from another basin because of both logistics and specifications.

That era is ending.

The New Westbound Build-Out: It’s Not Just One Pipeline

Western Gateway isn’t alone. In recent months, multiple midstream players have announced projects to move refined products west, turning what once looked like a single corridor into a competitive race that will reshape basin economics.

| Project / Sponsor | Route | Capacity & Status | Target In-Service | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun Belt Connector (ONEOK) | El Paso → Phoenix | 24-inch greenfield pipeline; ~200 Mb/d initial; scalable; open season launched | Mid-2029 | Pushes PADD 3/2 barrels into Arizona with room to grow |

| Western Gateway (Phillips 66 + Kinder Morgan) | Borger → Phoenix (new-build) + SFPP West reversal into SoCal + Gold Line reversal east→west; CALNEV connection to Las Vegas | Binding open season; integrated new-build + reversals | By 2029 | Creates first end-to-end PADD 2/3 → California corridor |

| HF Sinclair (evaluation) | PADD 4/5 expansion concepts (Nevada & California markets) | Multi-phase refined-products expansions under review | TBD | Adds competing westbound optionality from Rockies / Intermountain |

Why it matters:

A single westbound path could have been dismissed as outage insurance. Multiple scalable corridors change the behavior of markets as they cap outage windfalls, compress rack premiums, and accelerate spec convergence (CARB) as out-of-state refiners invest to serve a newly contestable, premium market.

Phoenix from “Tweener” market on Basin Edge to Basin Corridor

Phoenix historically sat “between” two supply basins — not quite West Coast, not quite Midcontinent. The new system turns Phoenix into a throughput market, not a terminal endpoint. The real destination becomes California, with Phoenix increasingly functioning as a pressure-release valve and staging ground for westbound supply.

That matters because pricing dynamics follow basin geometry.

When California is isolated, prices rise.

When California is connected, prices normalize.

These pipelines are the beginning of normalization.

Why This Is a Strategic Threat to California Refiners

The premium historically embedded in California retail and wholesale markets is a function of scarcity economics, a closed basin with limited substitutes. Yes, regulators make this a lot worse for consumers and competition, but our industry overcomes those kinds of barriers over time. Once outside supply enters at scale, scarcity disappears.

Refiners in the state can no longer count on capturing premiums just tied to geography. Retailers may still enjoy premiums, particularly in urban markets where regulation is all but prohibiting construction of new sites, but those “red” parts of the state we may see new entrants chasing those retail premiums down a good bit.

The competitive threat is not immediate volume displacement, these pipes are not capable of that much throughput, it is margin compression.

Once margin compression begins, two second-order forces will follow:

- Reduced capital investment in local refining (why reinvest if the moat is shrinking?), and

- Economic incentives for rationalization — not forced shutdowns, but voluntary retreat.

In other words:

These pipelines don’t directly shut a refinery, with recent closures the first pipeline may just replace what was just lost volumetrically. But, it changes the math so that more shutdowns become rational if not inevitable.

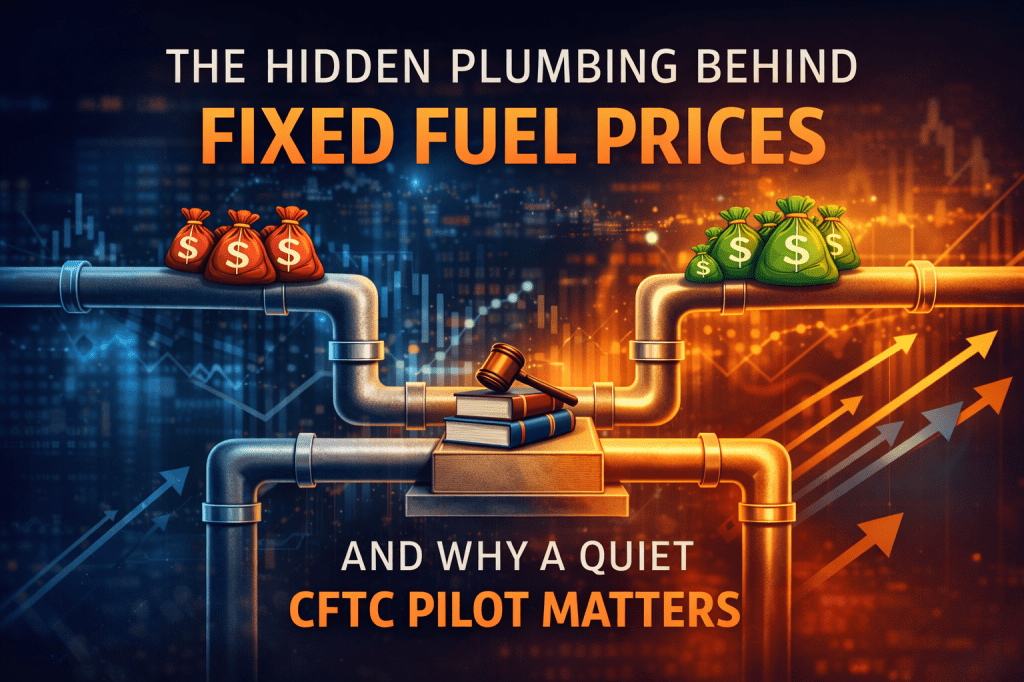

The CARB Spec — The Last Remaining Moat

The one remaining barrier is fuel specification compatibility. California’s CARB formulation is more stringent than conventional gasoline and diesel, which has long protected in-state refiners from direct substitution.

But in every market where a high-premium spec exists, once pipeline access is available, out-of-region refiners sooner or later build the spec. The premium justifies the reconfiguration and blending needed to hit the spec.

Phase 1: Basin connection

Phase 2: CARB blending adoption

Phase 3: Margin convergence

Once Midcontinent or Gulf refiners begin manufacturing CARB barrels regularly, California is no longer a special market, it is simply another premium destination with pipeline optionality.

And at that moment, the refinery moat disappears.

The Policy Irony

California has spent years constraining local refining capacity through regulation, permitting friction, and capital deterrence. The intent was to push the market toward decarbonization.

But scarcity premiums create market signals. The higher the price delta, the stronger the incentive becomes for outside refiners to build pathways in.

The state tried to discourage refining and in doing so made the market more attractive to out-of-state refiners than ever before. Policy aimed at local reduction is leading instead to import substitution, not demand decline.

Personally, I love the irony. For years, Californians have been told that volatility and high prices were the cost of environmental leadership. While regulators have certainly not done consumers any favors there was always a high cost of being such a large but isolated market. A market without alternative suppliers is not a “market” it is a captive pricing zone.

Western Gateway is just maybe the first real escape hatch for fuel consumers worn down by over a decade of very high prices.

Ultimately, it is always competition, not policy, that eventually gives consumers relief. The core irony is that the state did not allow this relief, the state forced the conditions that made it profitable for outside suppliers to build the access.

A New Competitive Era

First geography and later regulatory policy insulated California. That era is ending. Western Gateway, Sunbelt and Sinclair’s projects are not just a new set of pipelines, but a fulcrum. They will change California from a closed market to a contested one. In our ever efficient industry once a market becomes contestable, it eventually becomes commoditized .

This is the real significance of Western Gateway and these other projects:

- It is the first infrastructure step in the unwinding of refinery isolation.

- It shifts pricing power outward.

- And it forces a long-term reckoning not on environmental grounds, but on economics.

California is no longer an island, it is becoming a new endpoint of a national system. A national system that is the most scaled and efficient in the world. There will sure to be outcries from the environmental crowd that this is just extending our dependence on fossil fuels, but I believe most consumers who are the ones actually paying the freight. Maybe, just maybe, they will simply say thank you for the price break. From our industry: You are welcome.

Leave a comment