I have a curious hobby of watching for these quiet regulatory changes that seem to happen around holidays. Heading into Christmas this week I wasn’t disappointed as the CFTC released a statement and started a pilot that should reduce the costs to manage exposure to volatile fuel prices.

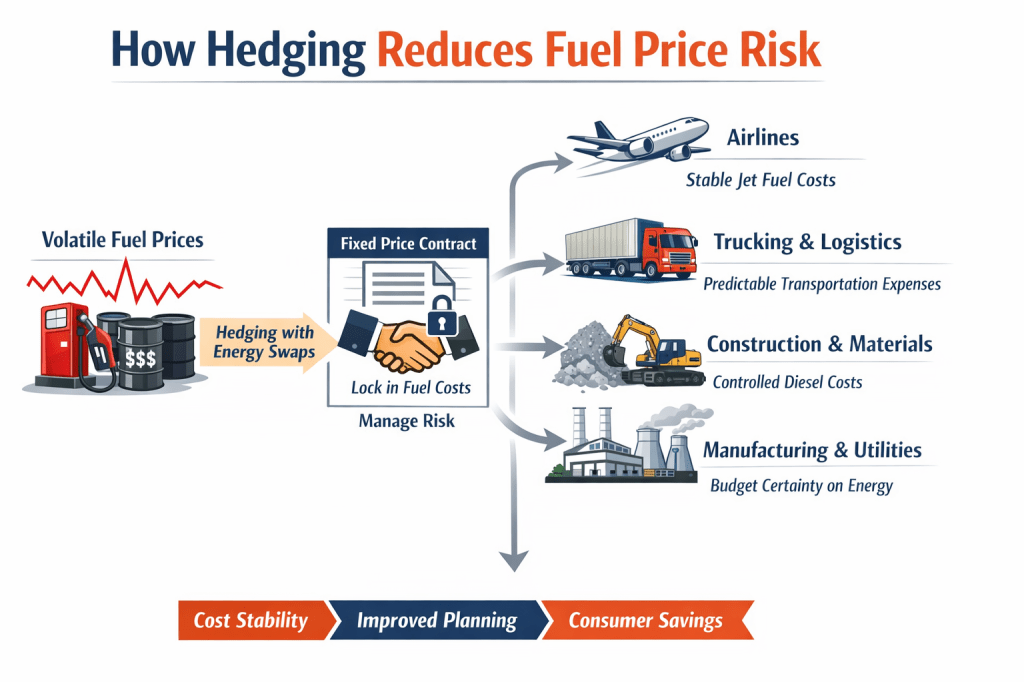

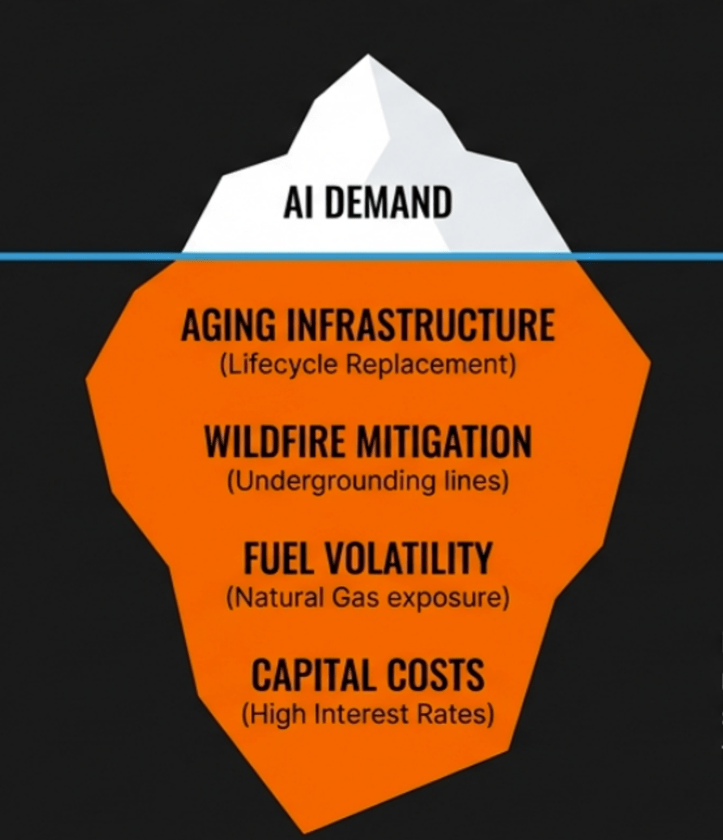

Fuel price volatility doesn’t just impact oil companies and traders. It hits the budgets of operating companies across the U.S. economy, often in ways that are hard to pass through quickly. If your business moves goods, people, or materials, fuel is not a “market price.” It’s a core operating expense and when prices swing, it creates real second-order effects: contract repricing, margin compression, delayed projects, and uncertainty that makes planning harder.

That’s why hedging exists. Not to speculate, but to turn unpredictable into the predictable. To take the input costs for something that a business has no choice but to buy regardless of the price, like fuel, and turn it into plan not a hope that things will work out.

Why this matters — even if you’ve never hedged fuel before

Most businesses don’t think of themselves as participants in energy markets, but fuel is a material input to transportation, manufacturing, utilities, and logistics. Fuel price volatility hits margins, planning, and end product pricing decisions.

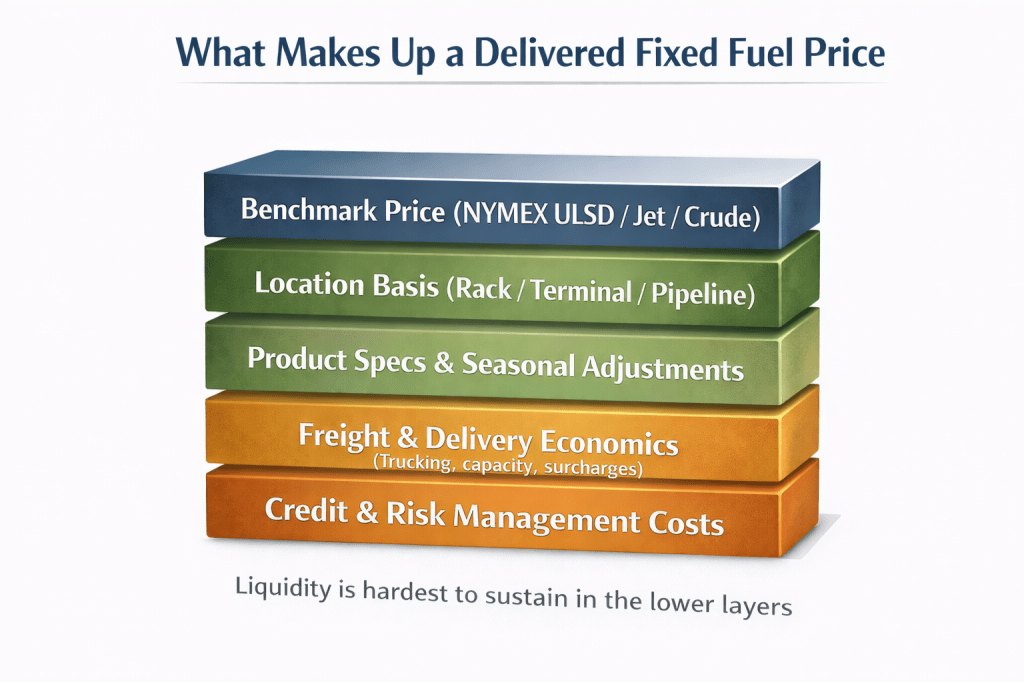

What looks like a simple “fixed fuel price” is actually a layered structure that converts global energy markets into a delivered, location-specific operating cost. That structure depends on liquidity across multiple markets, not just futures. The CFTC’s pilot program targets this friction point by testing whether recalibrated rules can improve real-economy risk management outcomes without sacrificing oversight.

FUEL PRICE RISK IS AN OPERATOR’S PROBLEM, NOT A TRADER’S HOBBY

Just a few examples:

A regional food distributor running refrigerated fleets can’t “wait out” a diesel spike. Fuel swings hit margins immediately.

A construction firm or their aggregates producer runs hauling and equipment where diesel is a meaningful cost driver on every job.

Airlines manage jet fuel price risk because it can overwhelm pricing and network planning if left uncontrolled.

Trucking and logistics often operate on thin margins where fuel surcharge mechanisms lag reality and contract terms don’t always reflect spot moves.

These companies aren’t looking for upside or trying to gamble on speculative derivatives. They are trying to avoid downside scenarios that disrupt pricing, staffing, capital spending, and customer commitments.

WHY PEOPLE MISUNDERSTAND HEDGING

When operators hear “hedging,” many assume it means buying or selling futures contracts on NYMEX.

That’s one tool and it’s a very important one, but it’s not the full story.

Most end users don’t buy “NYMEX diesel.” They buy delivered diesel at a specific location, under specific supply and logistics constraints, priced off specific market indexes.

So the real question isn’t “Can I hedge diesel?” It’s, “Can I hedge the delivered cost of diesel at my locations in a way that matches how I actually buy fuel?”

That’s where complexity comes in and where liquidity has become harder to sustain.

A “FIXED” DELIVERED FUEL PRICE ISN’T A SINGLE PRICE

A fuel supplier may offer an end user a fixed price program that feels simple:

“You can buy diesel at $X.XX/gal for the next quarter.”

But behind that number is a layered structure converting a benchmark commodity market into a delivered, operationally real price.

This is why end-user hedging isn’t just “futures.” It’s a package that transforms commodity price risk into an operating cost with predictability.

THE LAYERS BEHIND A DELIVERED FIXED FUEL PRICE

Benchmark price risk – Most programs start with a widely traded benchmark (typically tied to a futures market). This is the most visible and liquid part of the hedge.

Location and basis risk – End users, or the fuel distributors that supply them, buy at racks, terminals, or pipeline locations not at the benchmark delivery point. The difference is basis, and it can and does move independently of the futures market.

Product/spec differences – Fuel specifications vary by region, season, and regulation, creating real pricing differences relative to a generic benchmark.

Freight and delivery economics – Delivered pricing includes real logistics: trucking costs, capacity constraints, and contractual mechanisms that function like surcharges.

Credit, collateral, and risk management costs – The final fixed price reflects counterparty exposure, margining/clearing dynamics, balance sheet usage, and the cost of intermediating risk.

The key point that relates to this CFTC pilot is that liquidity declines as you go down this stack. And the lower layers are where commercial end users, that actually use the fuel, live and work.

WORKING EXAMPLE

Fixing delivered diesel for a Midwest food distributor (illustrative example simplified for clarity)

The business: A regional food distributor operates a fleet of refrigerated trucks across the Midwest. Diesel is one of its largest variable costs, and customer pricing is often set quarterly.

Goal: Reduce exposure to diesel volatility for the upcoming quarter so the company can plan pricing and protect margins.

How the “fixed delivered price” gets constructed:

Step 1: Define the real exposure The distributor doesn’t buy “NYMEX diesel.” It buys delivered diesel at local terminals, trucked to facilities.

Step 2: Lock the benchmark price The supplier hedges the underlying benchmark (often tied to a NYMEX ULSD curve) to stabilize the core price component.

Step 3: Manage location (basis) risk Midwest rack prices don’t track the benchmark perfectly. Basis must be managed using swaps or negotiated differentials — where liquidity is thinner.

Step 4: Account for freight and delivery economics Delivered pricing includes trucking capacity and freight dynamics that can move independently of the benchmark.

Step 5: Price credit and risk management costs The supplier must price counterparty exposure, margining/ collateral impacts, and the balance sheet cost of warehousing risk.

Result: The food distributor sees one fixed delivered price per gallon. Behind it is a layered structure converting volatile markets into predictable operating cost.

Why this matters: when liquidity is constrained in basis, delivery, or bespoke structures, fixed-price programs become more expensive or unavailable.

FOCUSING DEREGULATION WHERE LACK OF LIQUIDITY ACTUALLY MATTERS MOST

Benchmark futures markets tend to be deep and transparent.

But the “real world” layers — basis, location-specific exposure, bespoke structures, delivered pricing — are where transactions are more customized and liquidity is thinner. These layers depend heavily on broker-dealers and intermediaries willing to intermediate risk and provide pricing.

When regulation raises the cost of participating in these markets, liquidity doesn’t retreat evenly it retreats first from the harder, customized edges of the market.

WHAT THE CFTC PILOT PROGRAM IS TRYING TO DO

The CFTC’s pilot program is aimed at increasing liquidity and hedging capacity tied to Energy Commodity End User Swaps, while adding monitoring and reporting so staff can oversee activity.

The policy logic is straightforward:

If the cost of serving end-user energy swaps is too high, dealers reduce activity or exit. Liquidity declines, hedging becomes more expensive, and operating companies pay more to manage risk (or can’t do it effectively).

CONCLUSION

Energy price volatility isn’t going away. What matters is whether operating companies have effective tools to manage it and whether those tools remain accessible beyond the largest players.

The CFTC’s pilot program doesn’t change how fuel is bought or sold physically. It tests whether recalibrating regulatory treatment of energy end-user swaps can improve liquidity in the layers that convert volatile benchmarks into predictable operating costs.

For non-traders, or those of us no longer trading, the signal to watch isn’t trading volume on an exchange. It’s whether fixed-price fuel programs become more competitive, more flexible, and more widely available to transportation- and energy-intensive businesses.

If the pilot succeeds, the impact won’t be dramatic headlines. It will show up quietly: steadier budgets, fewer pricing shocks, and less volatility passed through supply chains to consumers.

That’s not deregulation for its own sake. It’s restoration of a key financial infrastructure layer for managing risk in the real economy.

FURTHER READING: REGULATORY CONTEXT AND PRIMARY SOURCES

For readers interested in the regulatory mechanics behind the CFTC’s pilot program and the energy market rules it is addressing, the following primary sources provide useful context.

CFTC Announcement and Pilot Program

CFTC Press Release (December 19, 2025) Acting Chairman Pham Announces Pilot Program to Unleash American Energy Dominance Official announcement outlining the pilot program for Energy Commodity End User Swaps, including rationale, scope, and reporting requirements. https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases

Underlying Regulations and Market Structure

De Minimis Exception to the Swap Dealer Definition (Federal Register, 2018) Final rule establishing the permanent swap dealer de minimis threshold and the regulatory framework the pilot program is now testing in a targeted way. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/11/13/2018-24579/de-minimis-exception-to-the-swap-dealer-definition

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act – Title VII Statutory foundation for the modern U.S. swaps regulatory regime, including registration, reporting, and clearing requirements. https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/4173

Leave a comment