Rethinking Adam Smith Through Howard Lutnick’s Lens

First let me start out by saying how disturbing the “Liberation Day” spectacle was for me. For much of my academic and professional life, I accepted free trade as settled doctrine. Comparative advantage, specialization, and open markets were not merely theories; they were to be treated as near-laws of economic gravity. We learned them through Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and generations of economists who followed.

For a little background, as an undergraduate engineering student at Clemson I figured out that my tuition was the same even if I added classes that I didn’t need for my degree. Having loved the economics classes that I did take to meet requirements, I went on to take many many more just for fun, I loved the subject matter. I felt like I was learning how the world really worked in ways that the crisp math and calculations of engineering could never address.

So seeing those principles assaulted in such a circus like manner on April 2 was an affront to a lifetime of learning and belief. It was also contrary to what I had personally experienced when setting up our software engineering centers in India in the early 2000’s. We delivered far more for our customers than we could with just a US workforce because we could work around the clock. Our employees in India and in the US benefited and we all made more money.

Since listening to Trump directly is difficult and seldom yields a whole lot of insight, I have started tracking the output of both Scott Bessent and Howard Lutnick to try and discern the thinking and strategy, most of which is completely different than the sound bites that is all the press will cover.

So this past week listening to Howard Lutnick speak on the All-In Podcast forced into clarity for me the real question I have been wrestling with, what happens when one side plays by Adam Smith’s rules and the other does not?

Lutnick’s remarks, delivered not from an academic podium but from the inside of modern geopolitics, being in the room as he states it, challenge the assumption that global trade today resembles in any way the idealized system most of us were taught in all those economics classes. His worldview is not theoretical. It is being forged in rooms where trade, security, diplomacy, and capital flows collide in real time.

No I am not rejecting economics, nor is this a bombastic rejection of free markets. It is something more tactical and practical: a recognition that classical free-trade theory is woefully and structurally incomplete in a world dominated by strategic states, namely China, but the EU and others as well, rather than neutral markets.

As an energy guy with decades in what is and has never been a “free market” this shouldn’t be much of a jolt, but I think many of us believed that while our market wasn’t free of state and monopolistic manipulation, most others surely were. Seems while that was right for a time, maybe from post World War II until the global financial crisis in 2008, it hasn’t been anywhere near true in the past 15 to 20 years.

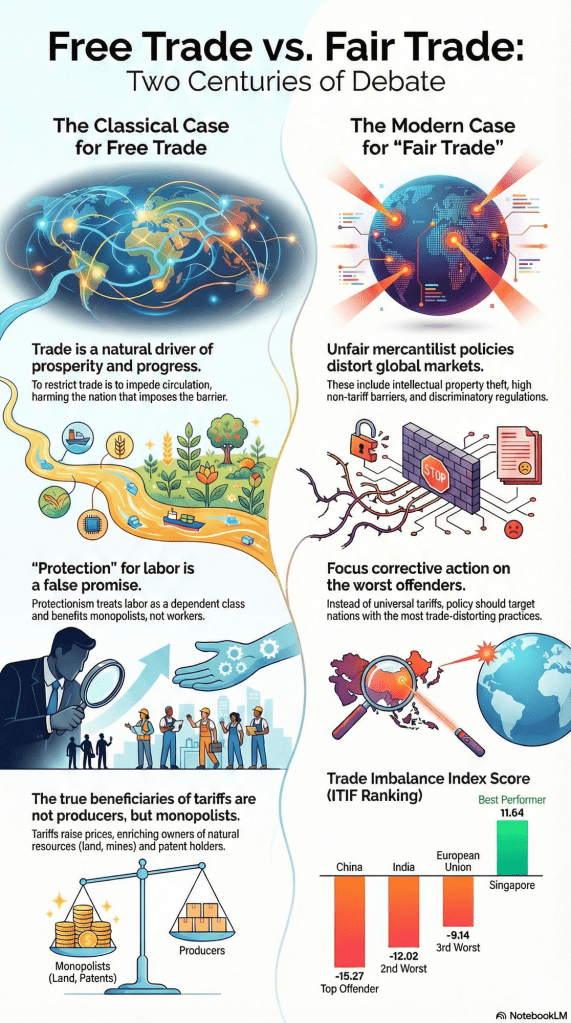

The Classical View: Comparative Advantage as a Universal Good

At the heart of classical economics lies a simple, powerful idea: nations prosper by specializing in what they do best and trading freely with others. Comparative advantage does not require fairness or symmetry, only efficiency.

Under this model:

- Trade raises aggregate welfare.

- Market signals allocate capital optimally.

- Political intervention distorts outcomes and reduces total surplus.

Implicit in this framework, however, is an assumption that states behave roughly like firms, responding to prices rather than wielding policy as an economic weapon.

Clearly that assumption no longer holds, if it ever did.

Mercantilism Never Left—It Just Changed Form

Mercantilism is often taught as a historical artifact: 17th-century kingdoms hoarding gold and protecting domestic producers. But modern mercantilism looks different. It is not about tariffs alone, it is about industrial policy, currency management, state capital, and strategic dependency.

Many major economies today subsidize “national champion” industries, use non-market financing and state banks, and restrict foreign access while demanding reciprocity. They treat supply chains as instruments of national power.

In that context, unilateral free trade becomes less a moral high ground and more a strategic vulnerability.

Lutnick’s perspective does not deny the benefits of trade. It questions whether one-sided adherence to free-trade norms remains rational when counterparties explicitly reject them.

Is the U.S. Becoming Mercantilist—or Merely Defensive?

Is the U.S. shifting toward mercantilism because it rejects free trade?

Or is it responding to an asymmetric system where free trade has been exploited by mercantilist actors?

From this lens, recent U.S. policies. —reshoring incentives, industrial subsidies, trade enforcement, supply-chain security, all look less like a rejection of Adam Smith and more like an attempt to restore the preconditions that make Smith’s framework viable:

- Competitive neutrality

- Market-based pricing

- Mutual openness

If comparative advantage presumes markets, then defending markets may require state action. That is not mercantilism in the classical sense. It is market preservation under non-market pressure.

Growth, Power, and the Return of Political Economy

Lutnick’s bold claim, that the U.S. could push toward 6% GDP growth this year, rests on a view many economists resist: that growth is not merely a market outcome, but a policy choice when capital, labor, energy, and security are aligned.

Classical theory separates economics from power. Reality does not.

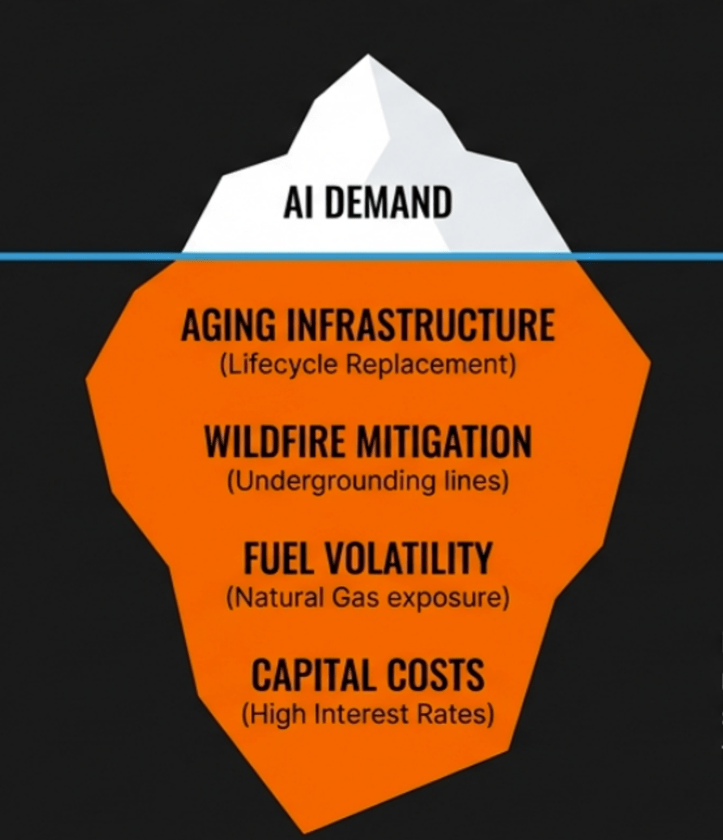

Energy independence, industrial capacity, logistics, and technology dominance are no longer side topics, they are core growth inputs. Ignoring that linkage may be elegant. It seems to also be very naïve.

A More Honest Synthesis

The real challenge to traditionalists, like me, is not that Adam Smith was wrong, but that his model assumed conditions that no longer universally exist.

A more realistic framework that I think we might have to accept:

- Free trade as a goal, not an axiom

- State intervention as a stabilizer, not a permanent substitute

- Comparative advantage as dynamic, not fixed

This is not an argument for protectionism without limits. It is an argument that open markets require enforcement, symmetry, and resilience, especially in energy, infrastructure, and strategic industries.

The Question We Should Be Asking

The debate should not be framed as free trade versus mercantilism.

It should be framed as:

Can a free-trade system survive when only some participants believe in it?

Howard Lutnick’s perspective is uncomfortable precisely because it forces that question into the open, away from textbooks and into the real world where economics, power, and national strategy intersect.

That is a debate worth having.

Further Reading and Research Sources, most not for the feint of heart when it comes to reading dense material.

🏛️ Historical & Policy Context on Mercantilism & Tariffs

U.S. International Trade & National Security (Barkey) – Discusses how mercantilist tactics can resurface in modern geopolitical contexts. Digital Commons

A Neo-Mercantilist Analysis of U.S. Foreign Policy – Academic lens on how U.S. trade policy under Trump was interpreted as neo-mercantilist. ResearchGate

From Navigation Acts to Tariff Wars – Discusses the modern return of mercantilist logic through strategic tariff use. Medium

Report on Manufactures (Alexander Hamilton) – Foundational U.S. historical policy advocating early industrial strategy rooted in what would be later described as mercantilist ideas. Sylla Review

📊 Critical Perspectives on U.S. Tariff Policy

The Trade Deficit Delusion: Why Tariffs Will Not Make America Great Again – Scholarly critique arguing tariffs are ineffective at correcting trade imbalances and could harm economic stability. Intereconomics

The Consequences of Trump’s Tariff Threats (Brookings) – Explains how tariff strategies can reflect older mercantilist thinking and the risks they pose. Brookings

U.S. Tariff Policy and WTO Challenges – A legal/economic analysis showing how protectionism has tested multilateral trade systems like the WTO. OxJournal

Dallas Fed: Tariffs & U.S. Policy Goals – Economic research showing the trade-offs tariffs create and why they don’t neatly deliver all policy goals simultaneously. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

📈 Free-Trade Advocates & Critics of Protectionism

Joseph Stiglitz on Free Trade & Protectionism – Nobel Laureate economist arguing that tariffs and reversals of globalization harm modern economies. Wikipedia

Trade Openness, Tariffs, and Economic Growth (G-20 study) – Empirical analysis linking openness with growth and pointing to negative correlations with tariff increases. arXiv

🧠 Strategic / Defensive Views on Trade Policy

ITIF’s Trade Imbalance Index – A think-tank resource highlighting barriers U.S. industries face and arguing for targeted actions in global markets. ITIF

PIIE Analysis: U.S. Demands, Not Rules, in Trade – Explores how the U.S. increasingly uses power rather than rules to influence global trade relations. PIIE

RSM’s “New Mercantilism” Discussion – Defines modern mercantilist strategies emerging in response to global friction and competitive pressures. RSM US

📚 Additional Suggested Classic & Comparative Works

Older tariff debates (Irwin, 1991) — Contextualizes protectionism within broader historical economics. American Economic Association

Link to the All In Podcast Episode – https://allinchamathjason.libsyn.com/howard-lutnick-how-america-can-hit-6-gdp-growth-in-2026

Leave a comment